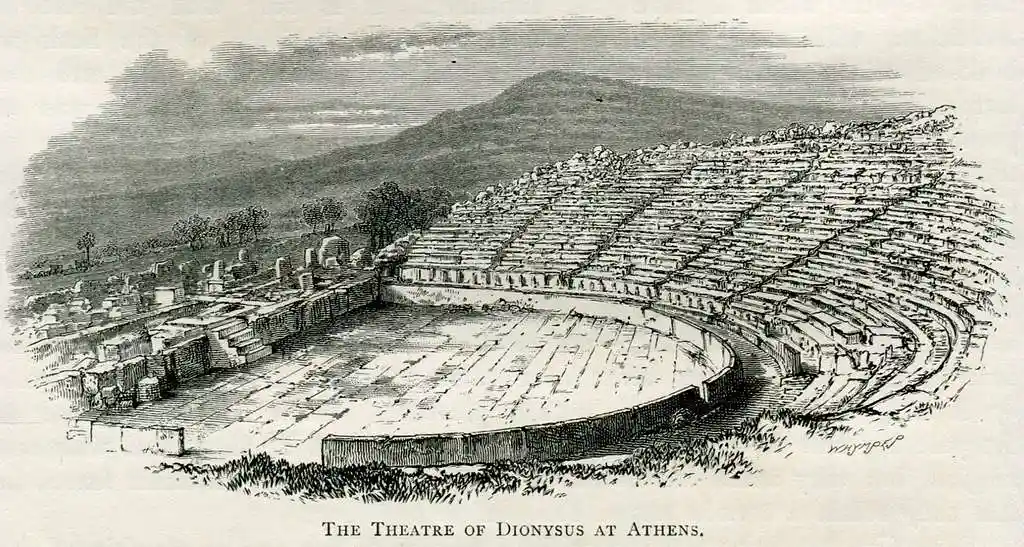

The Theatre of Dionysus is considered the cradle of Greek tragedy and comedy, being one of the oldest theaters in the world. Located at the foot of the Acropolis, it was the first theatre built of stone and hosted the festival of the Great Dionysia. Learn all about its history and what you will be able to see during your visit.

Entry to the Theatre of Dionysus is automatically included in the standard Acropolis admission ticket; no separate purchase is required.

No events or performances are held at the Theater of Dionysus. These events, usually concerts, are typically held at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, but it is currently undergoing renovations that will last three years. Both sites are open to tourists.

What can be found today are primarily the permanent architectural remnants of its successive reconstructions, from its archaic origins to its Hellenistic and Roman forms.

You can appreciate the stone and marble tiers that defined the cavea, a massive spectator space that could accommodate about 17,000 people.

Visiting the interior of the theatre means encountering the physical structure that witnessed the works of Aeschylus (a Greek playwright considered the first great representative of Greek tragedy), Sophocles (a Greek tragic poet), and Euripides (another tragic poet of this era).

The focus of your visit to the world’s oldest theater should be the Proedria, the front row, where the marble thrones reserved for civic and religious leaders are preserved. In front of them stretches the Orchestra, the circular performance area where the chorus sang and danced. Behind this, you will be able to observe the foundations of the Skene structure, or stage building, which served as the backdrop and changing rooms for the actors.

Early morning (right at 8am opening) offers soft light, minimal crowds, and comfortable temperatures. Late afternoon golden hour creates dramatic shadows on the carved marble thrones. Midday is worst—harsh overhead sun flattens details and summer heat becomes punishing. Tripods and drones are prohibited.

You cannot sit on ancient seats, and designated paths limit free wandering. Uneven marble surfaces demand sturdy footwear. Wheelchairs face significant challenges on the sloped terrain.

The Theatre of Dionysus was dedicated to Dionysus (or Bacchus in Roman mythology), one of the most popular and complex deities in the Greek pantheon, revered as the god of wine, the vine, fertility, religious ecstasy, and theater.

The son of Zeus and the mortal Semele, his cult was characterized by wild and unrestrained ceremonies (thiasos), which often involved rituals leading to mystical trance. His connection to theater is fundamental: the festivals held in his honor, the Dionysia, provided the religious and civic context in which Greek tragedy and comedy were born and developed, making the Theatre of Dionysus his most important place of worship in Athens.

The origin of tragedy is linked to the Dithyramb, a choral hymn that was performed in his honor during his festivals. Over time, these chants gradually became more and more theatrical.

Its construction dates back to approximately 534 BC, when dramatic contests were introduced in Athens. The Theatre of Dionysus has a fascinating timeline that’s actually more complex than it might seem at first glance.

In its early days, the theater it was very simple: a wooden stage and earth seating carved into the southern slope of the Acropolis. Over time, it became the main venue for Athens’ dramatic contests, where works by celebrated playwrights such as (those mentioned previously) Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes were premiered.

Throughout the centuries, the theater underwent numerous expansions and renovations. The most significant transformation took place around the 4th century BC, when, under the influence of statesmen like Lycurgus, it was completely rebuilt in stone. This monumental version reflected Athens’ cultural importance and matched the legacy of its great playwrights.

During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, the theater’s relevance diminished and, eventually, it fell into disuse. In addition, the theatre was rediscovered and partially excavated in the 19th century.

The Theatre of Dionysus was built into a natural hollow on the southern slope of the Acropolis, which provided it with excellent acoustics. The theater was divided into three main sections: the Orchestra, the Skene (stage building), and the audience seating area, known as the Theatron or Cavea.

The Orchestra was the circular area where the chorus performed their songs and dances. The Skene was located behind the Orchestra and was the building where the actors performed, serving as a raised platform and a backdrop. The seating area (Cavea) was divided into sections (cunei), with the front row, known as the Proedria, reserved for dignitaries and priests, while the rest of the tiers were open to the general public.

The Theater of Dionysus was the site of many famous performances, including the premiere of Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy in 458 BC, Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex in 429 BC, and Euripides’ Medea in 431 BC. The theater was also the site of the Dionysia festival, a major religious and cultural event that featured dramatic performances, poetry recitations, and musical contests.

The Theatre of Dionysus contains the oldest surviving stone theatre in the world and the birthplace of Western drama.

Located on the southern slope of the Acropolis in Athens, the Theatre of Dionysus preserves approximately 20 of its original 64-78 seating rows, 67 marble VIP thrones, Roman-era relief panels, and foundations spanning eight centuries of construction.

Every surviving play by Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes premiered at the Theatre of Dionysus beginning in the 6th century BC. The visible remains represent layers from the original wooden structure of 534 BC through Roman renovations under Emperor Nero around 61 AD.

The Cavea, or seating area, of the theater is still visible today. Specifically, these are the semicircular rows of stone seats that once held up to 17,000 spectators.

This distinct geological depression allowed the architects to exploit the natural acoustic and visual properties of the hill. The extant shape is a result of the Lycurgan reconstruction (338–326 BC), which formalized the auditorium into a steeper, permanent stone structure capable of holding thousands of spectators.

The Skene, or stage building, is also partially visible. During your visit to the Theatre of Dionysus, you can see the remains of the foundations and the base of the stage, where the actors once performed.

While the Roman-era superstructure is entirely lost, the foundations dating to the 5th century BC remain. These stones once supported the theatrical machinery, including the mechane (crane) used by Euripides to lower gods onto the stage (“deus ex machina”).

The Orchestra, or circular area in front of the stage, was used by the chorus during performances. The surface you walk on today is a Roman modification commissioned by Emperor Nero around 61 AD. It features a pavement of varicolored marble slabs arranged in a central rhombus pattern.

At the exact center of the orchestra lie the remains of the thymele, the altar dedicated to Dionysus. Before any dramatic performance began, officials poured libations here to the god of wine and ecstasy. The presence of the altar underscores that ancient theatre was primarily a ritualistic religious event rather than secular entertainment.

The Theatron (“seeing place”) designates the tiered limestone seating rising from the orchestra.

Approximately 20 of the original 64-78 rows survive today. The seats are carved from Piraeus limestone, with each bench measuring roughly 33 centimeters deep and etched lines marking a cramped 16-inch width per spectator. The surviving lower section (ima cavea) held the general citizenry, while the lost upper section (summa cavea) extended all the way to the rock face beneath the Parthenon.

The Prohedria are the 67 marble VIP seats located in the very first row immediately surrounding the orchestra. These seats were reserved for priests, archons (magistrates), and distinguished citizens. Unlike the limestone benches behind them, these thrones feature comfortable backs and armrests designed in the klismos style. While the current physical seats are largely Roman-era copies (1st century BC–1st century AD), they preserve the form of the earlier Greek originals.

The central throne in the Prohedria row belongs to the High Priest of Dionysus Eleuthereus. This seat is larger and more ornate than the others, carved from premium Pentelic marble.

Detailed relief carvings decorate the throne, including bunches of grapes, satyrs, and lion-paw feet, symbolizing the deity. A legible inscription on the base identifies the occupant as the “Priest of Dionysus the Liberator.” This seat positioned the priest as the god’s representative, effectively “hosting” the festival.

The Katatome is the monumental vertical cutting in the bedrock of the Acropolis located high above the surviving rows. This artificial cliff face marks the original upper boundary of the theatre’s seating capacity. The sheer rock wall provides evidence of the immense scale of the ancient auditorium, which once extended far higher than the current ruins suggest.

Located near the theater, the Choregic Monument of Thrasyllos (320 BC) is a well-preserved monument that was built to commemorate a victory in a choral competition. It features intricate carvings and reliefs that depict scenes from the competition.

The Sanctuary of Dionysus Eleuthereus lies directly south of the theatre complex. This sacred precinct houses the foundations of two temples: the Archaic Temple (6th century BC), which held the wooden cult statue of the god, and the Later Temple (4th century BC), built to house a gold and ivory statue by Alcamenes. These ruins mark the ritual origin point of the festival.

The Acropolis ticket grants visitors access to the archaeological site of the Acropolis and its slopes, including the Parthenon, the Theater…

The Parthenon is an iconic symbol of ancient Greek civilization and a masterpiece of classi…

On Athens’ Acropolis, there is a stunning and well-known ancient Greek temple called…